Don't give them what they want.

"You should not give the audience what they love, but what they might love."

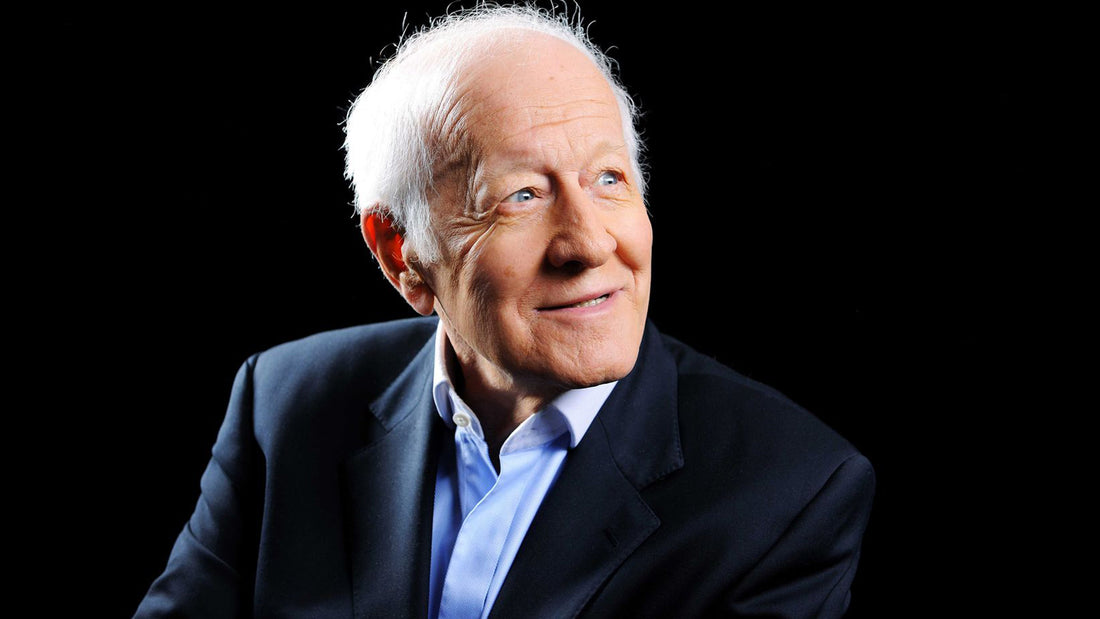

This quote from Jacques Chancel has resonated with me for many years. Although Chancel was never a magician—he was a renowned French journalist and cultural critic—his words seem to apply to all forms of art, including our own.

Since there's an inherent element of surprise and impossibility in magic and mentalism performances, the audience's reactions are often overwhelmingly positive, because what they see is both entertaining and inexplicable. And yet, there is always the temptation to stick to what immediately pleases: tried-and-true effects, hackneyed jokes, and formulas that have already proven successful. This is akin to giving the audience what they already love, without ever daring to offer them what they might love.

I often hear fellow magicians say they perform certain tricks because "people love that stuff!" Sometimes, these comments come with a hint of negativity toward the trick itself—or, worse, toward their own audience—as if these magicians believe that spectators don't deserve something better. Sure, I agree, "people love that stuff"... But perhaps that very same audience, in that same given time (the time of an effect or a show), could have discovered and appreciated something even better, more personal, and more enriching.

This tension between meeting immediate expectations and daring to innovate isn’t limited to magic. In cinema, for example, a film can generate astronomical box office returns and be deemed a commercial success, yet that doesn't necessarily place it in the realm of "great cinema." On that note, the legendary director Martin Scorsese once remarked in an interview that superhero movies do not constitute cinema. For him, cinema is built upon a rich artistic language: it is about exploring narrative, emotional depth, and the expression of the human condition. In his view, superhero films often settle for a visually spectacular form of entertainment—a sort of moving amusement park—without engaging those essential cinematic dimensions.

The dilemma is clear: should we follow the audience's expectations, or venture down new paths that might enrich them, even if immediate success isn’t guaranteed? In magic, the audience only sees the tip of the iceberg: the illusion, the presentation, the spectacle. They remain unaware of the tireless work, the quest for the most original method, or the countless hours spent perfecting every detail to create an experience that goes far beyond mere entertainment. Had I confined myself to "what the audience loves," I would never have dared to talk about Hiroshima or share some of my personal stories during the illusion show I performed 200 times in Paris from 2017 to 2019; fortunately, the audience seemed to appreciate the different tone and the emotional investment I brought to the performance. Had I confined myself to "what the audience loves," I would not have taken the risk of inventing Haiku, a book test using 17th century Japanese poetry!

Ultimately, it’s about finding a balance between the audience’s judgment and the artist’s vision. The audience is essential—it provides immediate feedback and shows us what resonates, what captivates. But the artist is the one who dares to innovate, who seeks to broaden horizons, and who invites the audience to discover new emotions and insights.

Trust yourself. Don’t always give in to commercial imperatives. Dare to offer your own approach, to pursue what the audience might love—not just what they already do. It is in this quest for authenticity and innovation that the true magic of our art lies.